The ring binder that shaped conservation as we know it

New details have emerged about how the global system for classifying endangered species - which forms the bedrock for modern conservation began with a humble ring binder and loose-leaf sheets; influenced by WWT's founder, Sir Peter Scott.

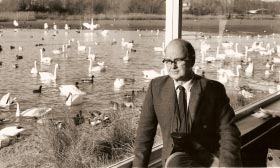

50 years ago there was no way to collate data from research or anecdotes around the world to build a picture of which species were endangered. But Sir Peter Scott, founder of the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust, and one of the founding fathers of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) was desperately worried about what was happening in the world and the future of wildlife.

50 years ago there was no way to collate data from research or anecdotes around the world to build a picture of which species were endangered. But Sir Peter Scott, founder of the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust, and one of the founding fathers of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) was desperately worried about what was happening in the world and the future of wildlife.

Conservation in those days was even more difficult than it is today, as data was scarce and communication was slower, making it hard to contact others in the scientific community and share results.

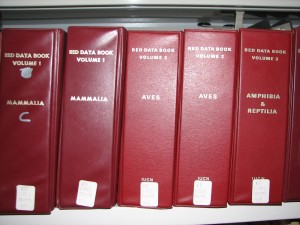

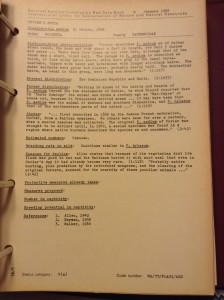

It seemed, as a logical minded ex-military man, that categorising species and their status was a good place to start. These hand-written, loose-leaf sheets in a ring binder were called the Red Data books, and each one contained information on a species, separated in proper categories, detailing how endangered they were and what was known.

It seemed, as a logical minded ex-military man, that categorising species and their status was a good place to start. These hand-written, loose-leaf sheets in a ring binder were called the Red Data books, and each one contained information on a species, separated in proper categories, detailing how endangered they were and what was known.

Despite Sir Peter’s wildly ambitious standards, he probably never dreamt that they’d form the basis of every other conservation programme of the future. Decades later, these basic yet functional books evolved into the much slicker, more modern IUCN Red List, now the international standard for evaluating the conservation status of plant and animal species.

From its small beginning, The IUCN Red List has grown in size and complexity and plays an increasingly prominent role in guiding conservation activities of governments, NGOs and scientific institutions. The Red List now covers over 76,000 species – a huge success growth from its humble precursor, the Red Data books.

Cassandra Phillips, who worked with Peter Scott as an International Conservation Assistant from 1981-1989 saw firsthand how passionate he was about saving species:

Cassandra Phillips, who worked with Peter Scott as an International Conservation Assistant from 1981-1989 saw firsthand how passionate he was about saving species:

“Peter Scott was a brilliant communicator in so many different ways. He had a loose leaf page for each endangered species, separated in proper categories, how endangered they were, what was known, as a basis for action.

Maybe it was partly his training in the war; he had a very organised mind and he just realised that the scientific basis of conservation and trying to help endangered species was crucially important – so the facts were important, and this was a wonderful visual way of getting facts across to people.

“Peter was inspiring, he would galvanise everybody, and it was always a question of “let’s do it now”. If he thought we should get in touch with somebody about a particular campaign whether they were a broadcaster, a businessman or royalty, he’d just say ‘Let’s see if they are there now, where’s the telephone number?”.Environmental organisations need a Peter Scott. He really was, as David Attenborough called him, the Patron Saint of Conservation.”

“Peter was inspiring, he would galvanise everybody, and it was always a question of “let’s do it now”. If he thought we should get in touch with somebody about a particular campaign whether they were a broadcaster, a businessman or royalty, he’d just say ‘Let’s see if they are there now, where’s the telephone number?”.Environmental organisations need a Peter Scott. He really was, as David Attenborough called him, the Patron Saint of Conservation.”

Working with IUCN on the Red Data books, was however, only one of Sir Peter Scott’s many achievements. Sir Peter achieved what many could never dream of in a lifetime; finding success as a author, TV presenter, Olympian, conservationist leader of WWT and WWF, and also a husband and father. Sir Peter was also an acclaimed painter who spent hours every day sketching things he saw in the natural world. He also sketched both WWT’s swan logo, and WWF’s panda logo.

Working with IUCN on the Red Data books, was however, only one of Sir Peter Scott’s many achievements. Sir Peter achieved what many could never dream of in a lifetime; finding success as a author, TV presenter, Olympian, conservationist leader of WWT and WWF, and also a husband and father. Sir Peter was also an acclaimed painter who spent hours every day sketching things he saw in the natural world. He also sketched both WWT’s swan logo, and WWF’s panda logo.

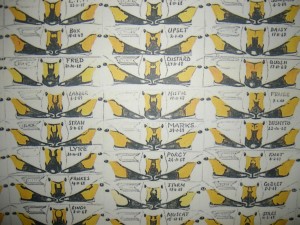

Perhaps the most well known of Sir Peter’s achievements however was in 1964, when herealised that each individual Bewick's swan could be identified by the unique pattern of yellow and black on its bill, so he began sketching the bill patterns of the Bewick’s swans that came to Slimbridge every winter. This started one of the longest-running single species studies in the world, and enabled detailed studies into the behaviour of these threatened swans, something which continues at WWT today.

Perhaps the most well known of Sir Peter’s achievements however was in 1964, when herealised that each individual Bewick's swan could be identified by the unique pattern of yellow and black on its bill, so he began sketching the bill patterns of the Bewick’s swans that came to Slimbridge every winter. This started one of the longest-running single species studies in the world, and enabled detailed studies into the behaviour of these threatened swans, something which continues at WWT today.