Higher risk to swans from lead poisoning

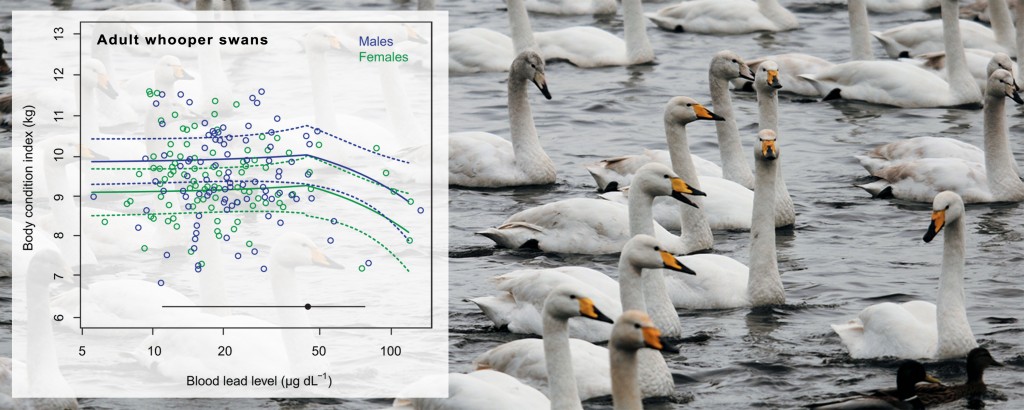

The health of swans in Britain is being affected by lead poisoning at lower doses than previously recognised, suggests new research by the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT) and the University of Exeter. The study investigated levels of lead in the bloodstream and found they were related to reduced body condition of whooper swans.

The swans’ body weight is critical for getting them through cold weather, and for giving them the strength to migrate from Britain back to Iceland in the spring and then breed successfully.

260 whooper swans were caught and tested by WWT in Lancashire and Dumfriesshire. The study showed significantly lower body conditions in birds whose blood lead level was above 44 micrograms per decilitre - lower than previously recognised thresholds of 50-100 micrograms per decilitre.

10 per cent of the swans in the study had lead levels above the level associated with significant loss of condition. The study shows how sensitive birds can be to lead poisoning as health effects can be seen at even relatively low levels of this toxic substance. Apparently healthy swans may in fact be suffering from the effects of lead poisoning.

The swans are exposed to lead by eating spent shot, left on the ground after shooting, which they mistake for food or grit. A classic symptom of lead poisoning is paralysis of the gut making digestion of food ineffective and leading to loss of weight and energy reserves.

WWT Senior Ecosystem Health Officer, Julia Newth said:

“We know from this and previous studies that a high proportion of whooper swans are affected by lead poisoning in the UK. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised to find negative impacts at lower lead levels than previously thought as global research on a range of species recognises that there is no such thing as a safe level of lead.”

Professor of Animal Ecology at the University of Exeter, Stuart Bearhop said:

“This new scientific study provides important evidence that the exposure of British birds to toxic lead isn’t just a matter of how many might die. Others may be weakened by lead poisoning, and these health effects will almost always be invisible to the casual observer.

“It is clear we need to find additional ways to reduce the risk of wildlife exposure to toxic heavy metals by initiating best practice and changing the types of shot used in the countryside.”

The whooper swans were caught at Martin Mere in Lancashire and Caerlaverock in Dumfriesshire during the winters of 2010/11, 2012/13 and 2013/14. Six of the seven catches were made very late in the season, between mid-February and early March, with the seventh in mid-December. This ensured their blood lead levels most likely reflected their diet while overwintering in Britain, rather than residual levels left over from feeding in Iceland the summer before – lead works its way through the bloodstream and then the level drops after around 35 days as it deposited in other body tissues.

The body mass index of each bird was measured by plotting its weight against the length of its skull, which is a reliable indicator of skeletal size.

Whooper swans mate for life. There are around 30,000 individuals in Iceland, of which 40 per cent make the 900 mile migration to Great Britain every winter, and 52 per cent travel to Ireland.

Partial restrictions on use of lead were introduced in England in 1999 and Scotland in 2004 due to growing concerns about birds being poisoned by spent lead ammunition. It is illegal to shoot lead over the wetlands around both WWT’s test sites in England and Scotland, while in England it’s also illegal to use lead to shoot certain species. But WWT testing in the winter of 2013/14 showed 77 per cent of 102 ducks, sold as being locally shot in England, were still shot illegally using lead rather than an alternative non-toxic material like steel which is already reMoadily available. Many birds, including whooper swans, often feed in fields away from wetlands where it is still legal to shoot many species (depending on which nation) using lead ammunition.

You can read the full paper in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Environmental Pollution.

Find out more about our work tackling lead ammunition poisoning