Protecting our Bewick’s on the Tundra despite the global lockdown

While the world's population is in lockdown, nature is suffering no such restrictions. Bewick's swans Elroy and Hope, have recently been spotted off the Gulf of Finland as they complete the final leg of their epic 2,500 mile migration.

Photo by Anton Kubyshkin

It’s one of the world’s last great wilderness landscapes and one of the most inhospitable corners of the planet - the Russian arctic. During the dark winter months the sun rarely rises, temperatures fall to -40℃ and the tundra is a carpet of ice. Even in the summer wild storms lash the coast. It’s hard to imagine life existing on this seemingly barren landscape.

Swan paradise revealed

And yet for our Bewick’s swans, it offers the possibility of new life, and survival for a species recently (since 2015) classified as endangered in Europe. May heralds the start of spring here and as the snows melt they reveal the hidden tundra in all its glorious multi-coloured beauty.

For our swans this vast wetland wilderness offers a welcome safe haven and the perfect summer breeding grounds. And they’re well on their way.

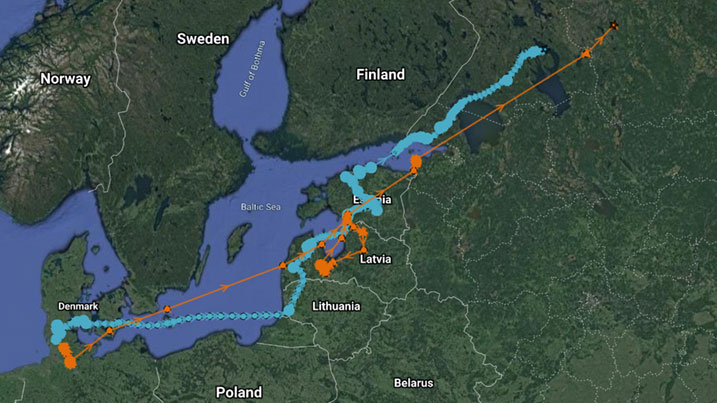

Already two of our tagged swans Hope (orange line on map above) and Elroy (blue line) have arrived in Russia along with hundreds of other Bewick’s and have recently passed through St Petersburg, refuelling on the Gulf of Finland.

They still have just over 1,000 km to go, flying across Russia and the densely forested Taiga with their last stop before reaching the tundra likely to be the White Sea in the north. On arrival at their breeding grounds our swans will be exhausted and will need to get busy feeding on the first flush of new spring growth, replenishing fat reserves, which have been burnt off during their long 4,000 km (2,500 miles) flight from Northwest Europe.

As the tundra awakes from its long frozen winter, it reveals a myriad of pools and a network of streams and rivers. Brimming with aquatic vegetation and insects, they’re enough to sustain millions of waterbirds with the protein they need for the breeding season. For a few months the tundra is transformed into one of the richest habitats on earth. Remote, fertile and safe, this is why our Bewick’s undertake such a perilous journey. Elroy and Hope know it’s these conditions that’ll give them the best chance of breeding success.

A race against time

Secretive and relatively scarce - the number of Bewick’s swans has dropped by a third in recent years and there are fewer than 21,000 left. They’ll have just a few months before they and any new young must be ready to make the long perilous journey back to a warmer winter. For the breeding Bewick’s, the brief arctic summer is a race against time. On arrival – around mid May – those already in pairs must quickly establish territories and start nesting. The rest of the ‘singletons' congregate in flocks, performing courtship ceremonies characterised by dramatic head-turning, stomping and wing-flicking displays.

Bewick’s swans pair for life and will only usually re-pair if their mate dies - the longest recorded partnership was a pair at Slimbridge called Limonia and Laburnum who were together for 21 years!

Challenges ahead

But it’s a time fraught with dangers, something WWT’s Dr Kevin Wood has been researching:

Over the many decades we’ve been studying the Bewick’s, we’ve seen a huge variation in the percentage of cygnets during the winter at our centres. In good years over 25% of swans arrive with cygnets. But in the worst years, cygnets make up less than 5% of the numbers.

So what threats do the swans and their young face? Predators like the arctic fox pose a danger. Also, the weather can have a big impact. If it’s too cold, Bewick’s may be forced to abandon their nests. Cold temperatures can also kill young in eggs that are left too long unattended. Colder summers also mean less vegetation for the swans and their cygnets to eat. "So we tend to see more cygnets surviving during warmer summers in the arctic," explains Kevin.

Conservation continues despite global pandemic

But one threat facing the swans is illegal hunting and this is an area where WWT is continuing to work hard to reduce the threats even during this time of global lockdown, as WWT’s Ecosystem Health & Social Dimensions Manager, Dr Julia Newth explains:

We’re already preparing for the swan’s arrival in the Russian arctic. The spring hunting season is about to start and we’ve created a whole tranche of materials to help hunters understand that the Bewick’s are protected. Reducing illegal hunting is a key focus for us this year.

Thousands of leaflets have just been printed and these will now be given to hunters across the region where the swans breed. They’ll provide a visual guide of the protected and huntable birds in the area, information about penalties incurred for breaking the law, a map of the no hunting zones plus instructions on how to report ring sightings. Posters will also be put up at key locations like hunting huts, airports and community centres. A new feature this year is a visual guide that can be downloaded onto phones.

Changing hearts, changing minds

This is all part of our ‘Swan Champion Project’ which is bringing together key influencers across the region including scientists, hunters, indigenous leaders, young people, teachers and local businesses, to convey the message that Bewick’s are protected and should not be hunted, as Julia explains:

Some hunters are not aware that the Bewick’s are protected and we’ve found that social pressure influences whether or not people intend to hunt Bewick’s. We want to work with our Swan Champions, as this grassroots network of passionate individuals drawn from across the Russian arctic, are going to be the best people to relay key messages and persuade their local communities to stop hunting Bewick’s. We think that this could be a powerful model to roll out to other sites across the migratory route where hunting is an issue.

Winning over hearts and minds was also the thinking behind a successful two-week tour of the Travelling Swan Exhibition that took place in February this year. Four remote communities in the Nenets Autonomous Okrug region of the Russian tundra were visited and the team travelled more than 1,200 km across snowy lands devoid of roads, ran 40 nature talks and 15 master classes.

You can read more about their adventures and achievements here.

Work is also underway to create a thirty-minute film. Last year a film crew visited the region and spent time talking to communities to understand their relationship with the swans and their importance in local culture and folklore.

But at the same time it will also show the sense of pride people have in their native wildlife and how local people are driving changes to help save the swans as part of an international collaboration of enthusiasts across the flyway. We want to celebrate this and use it to encourage everyone to work together to keep the Bewick’s in their landscape.

Adapting to a changing world

And how is the coronavirus affecting this work? Although the hunting season is starting, hunting will be restricted to local people only and therefore tourists that hunt will be excluded.

"This is a change," explains Julia "and we’ll have to see what impact it has on levels of hunting. Other than that, it’s business as usual. The leaflet drop is still going ahead, but if the situation changes on the ground, we have a Plan B and we’ll distribute the materials in digital form instead. Living in such an isolated place, the local communities there are incredibly resilient and adaptable. We have a lot to learn from them."

The Swan dynasties that need our help

WWT has been researching families of Bewick’s swans for over 50 years. Each year at Slimbridge researchers eagerly await the arrival of our winter visitors, identifying each one by their unique black and yellow bill pattern.

Discover more about our Bewick’s swan research here.

Some of these swan ‘dynasties’ can be traced back as far as the 1960’s when WWT’s founder Sir Peter Scott was painting the bill patterns he saw from his window. One such dynasty is ‘The Gamblers’. Their descendant Croupier was last seen aged 27 in the winter of 2018/19, and since he was born on the Russian tundra in 1992 he’s returned there every year. Between them, he and his partner of nearly 20 years, Dealer, have produced 29 cygnets. However this year we were visited by his adult son Croupie and mate Wheel.

Only time will tell if they, along with the thousands of other Bewick’s that migrate to the arctic tundra each year, manage to raise another successful brood this summer and return to Slimbridge with new cygnets. The team behind our Swan Champion Project can only watch and wait, confident they’re doing all they can to ensure the swans have the best possible chance of survival.