national press (the

Guardian

,

Telegraph

and

Times

), in other ornithological journals, and on the

websites of the Ramsar Bureau, the African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement (AEWA),

Wetlands International and the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust. So here we dwell on his long

service to

Wildfowl

, which he edited to an incredibly high standard for 21 years. He took on

the role of editor for

Wildfowl

19 in 1968, with Malcolm Ogilvie as co-editor, and continued

overseeing the journal up to and including

Wildfowl

39 in 1988, the year in which he retired.

Prior to Geoffrey becoming editor, the journal was published as the

Wildfowl Trust Annual

Report

and was divided into two parts: an account of the Trust’s activities for its Members, and

scientific papers on various aspects of wildfowl biology. The name changed to

Wildfowl

in

1968, the thinking behind the change (as described by Geoffrey and Malcolm in the editorial

at the time) being that the journal should focus on the study and conservation of wildfowl

(without “annual report” aspects included), in which case a title was required that reflected its

contents more accurately. By this stage

Wildfowl

was already established, regularly publishing

papers on the biology and conservation of ducks, geese and swans by authors other than

Wildfowl Trust staff, but under Geoffrey’s stewardship it became an acknowledged highly-

rated international publication, attracting papers from leading researchers of the day. An

overview of

Wildfowl

volumes 19–39 indicates that an impressive

c

. 420 papers were reviewed,

edited and published during this time, excluding progress reports from the Trusts’ various

research programmes. Moreover, in addition to his editorial responsibilities and his

2

©Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust

Wildfowl

(2013) 63: 1–3

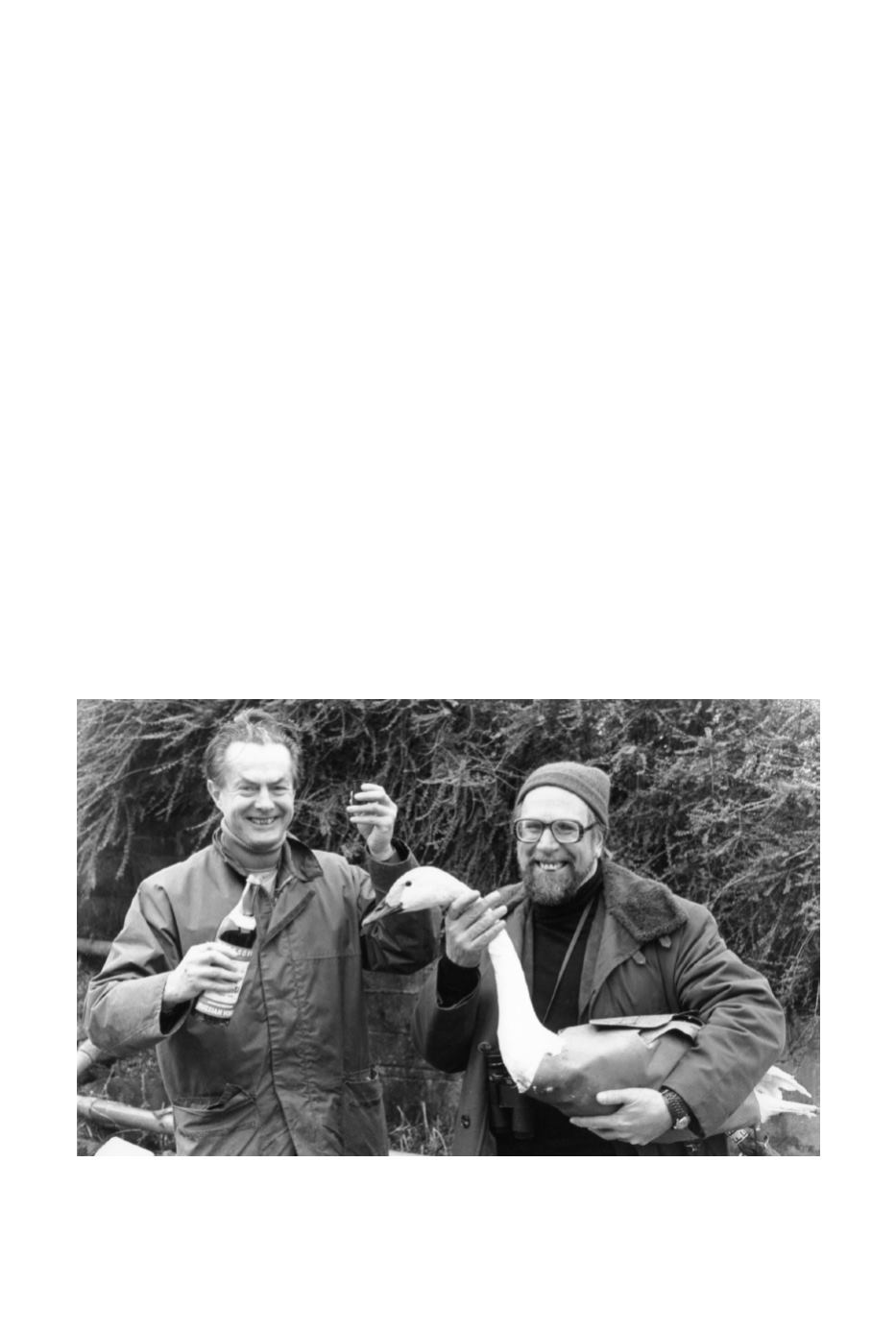

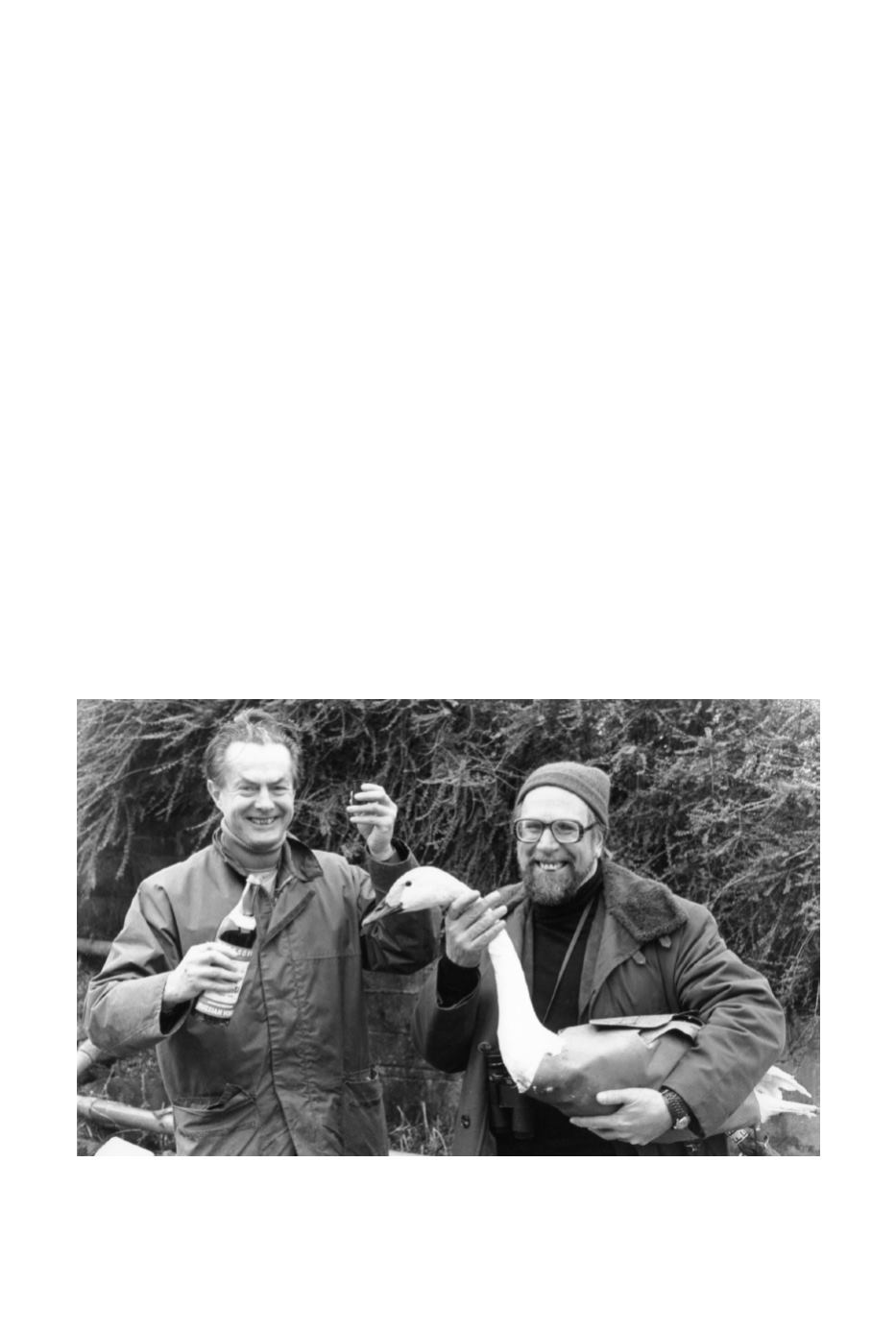

Photograph:

Geoffrey Matthews with Russian scientist Prof. Valdimir Flint (holding the Bewick’s Swan

named “Flint”) at a swan catch at Slimbridge in January 1979.