Summer research round-up #1

As regular readers of the Flamingo Diary probably know by now, I am a big fan of using the WWT birds for science, to make sure that there is a point to us keeping them at Slimbridge and the other centres that house collection birds. As we have so many flamingos, there are many different questions that relate to animal behaviour and ecology that we can ask. If you'd like to know more about how useful captive flamingos are to research, there is a good paper on the subject here: https://academic.oup.com/icb/article/33/2/117/153841/Feeding-Behavior-Aggression-and-the-Conservation

We talk a lot about the behaviour of the flamingos at Slimbridge, and that's because the big flocks are excellent tools for scientific research. We have birds of multiple ages and so we have a very natural set-up.

We talk a lot about the behaviour of the flamingos at Slimbridge, and that's because the big flocks are excellent tools for scientific research. We have birds of multiple ages and so we have a very natural set-up.

In previous posts, I have introduced you to some of the research that has been happening this year on various flamingos. And in this update I will share some findings with you. My MSc student, Dimi, has been watching the lesser and Andean flamingos in person, and my BSc student Abbie has been looking at behaviour of young greater and Caribbean flamingos using past photographs of the birds' behaviour. By running these projects over a long period of time, i.e. over each year and devoting several months to data collection we get a complete picture (or as complete-a-picture as possible) of the lives of our Slimbridge flamingos.

MSc student Dimitrina watches the Andean flamingo flock to look at differences in character between birds.

MSc student Dimitrina watches the Andean flamingo flock to look at differences in character between birds.

The close proximity of the Slimbridge birds allows for observation of individual characters at close quarters. You can see what I mean by this here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Im7-BW7E9nM

So what have we found this year? Both projects have had some very interesting findings and have provided useful information on what flamingos do and why. In this installment I will explain one of the projects, and in another post later in the month I will explain the other.

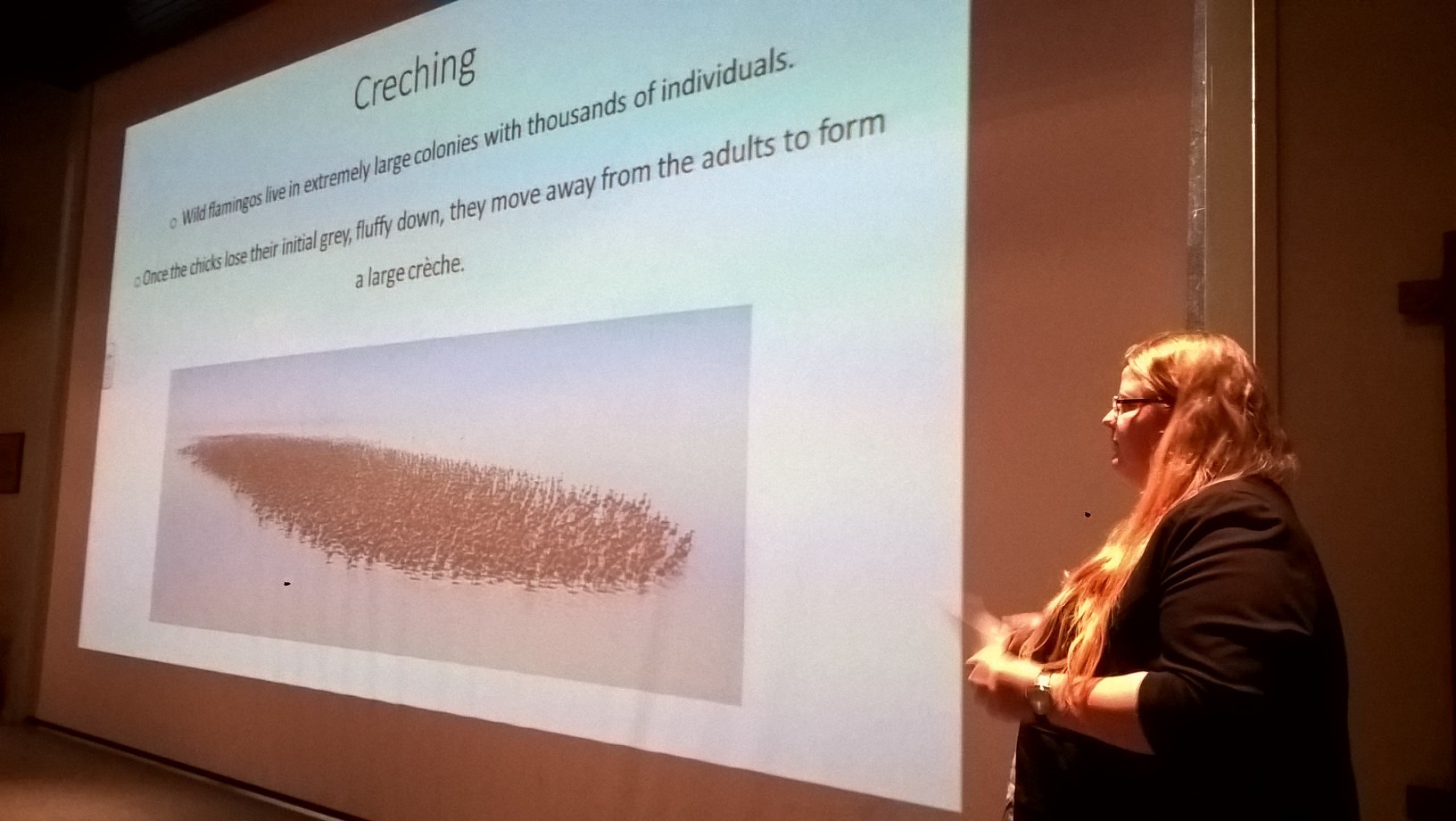

Abbie, who was investigating the behaviour of juvenile birds, was lucky enough to be selected to present her research at a zoo research conference at Edinburgh Zoo in July. Abbie trawled through hundreds and hundreds of images to collect data on where in each flock juvenile and sub-adult flamingos (in the greater and Caribbean groups at Slimbridge) were likely to be found. She was interested in seeing when birds were integrated into the flock as they grow from being fluffy, through their gawky "teenage" years, to beautiful adults. Here she is, in the photo below, explaining all about how flamingos creche their young to the conference audience.

BSc student Abbie presents the findings of her work at a zoo research conference in July.

BSc student Abbie presents the findings of her work at a zoo research conference in July.

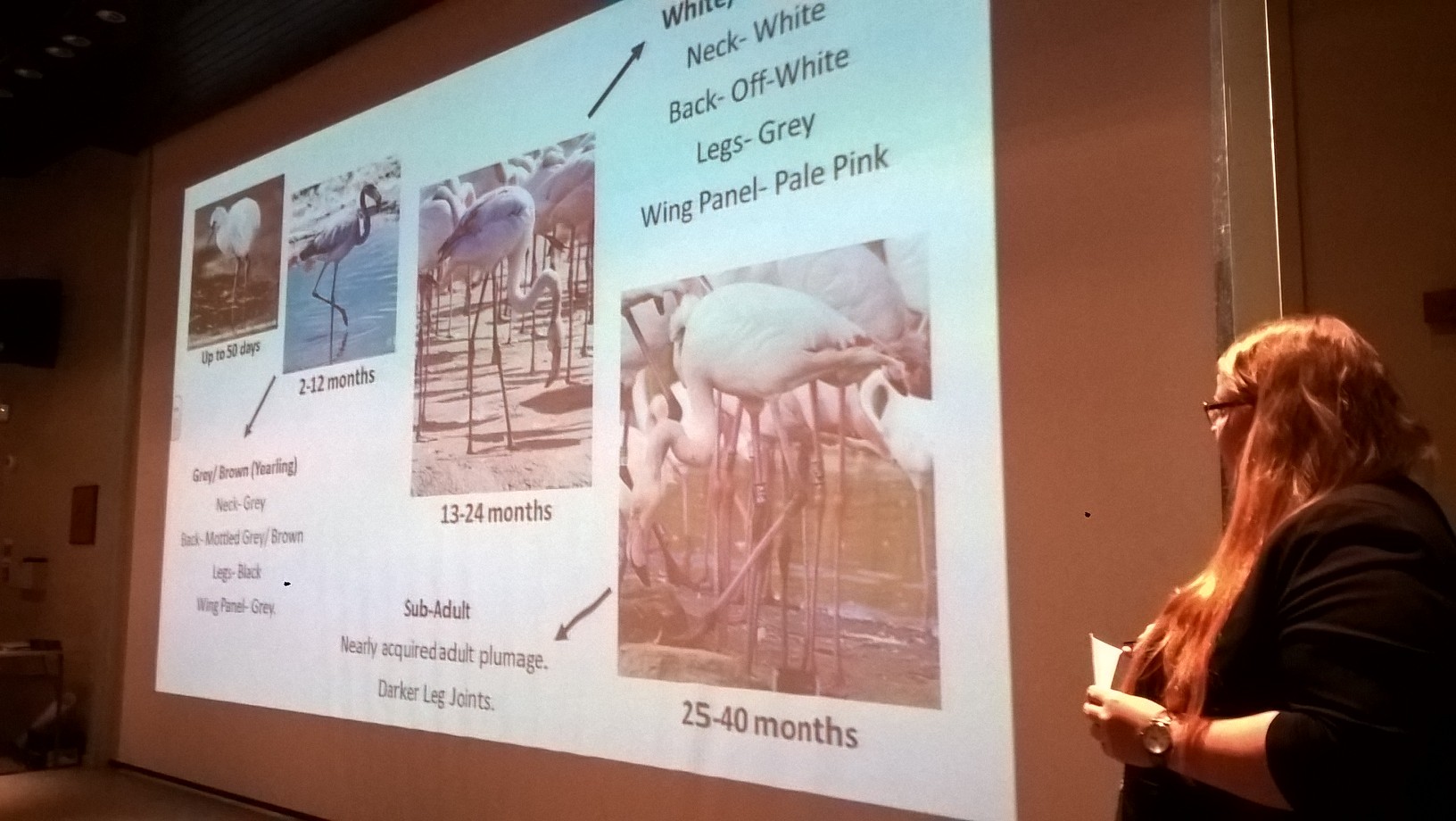

You have probably seen the colour that young flamingos are. After loosing their beautiful silver-grey down they beome a dull brown until, over the course of five or six years, they gain their eventual characteristic adult pink colour. Abbie classified stages of their plumage colour development and looked to see if this related to where they are seen in the flock. After all, a flamingo's flock is organised around the colours of the birds within it, so youngsters need to get to be the right colour before they "fit in". Or at least, that was my hunch when thinking up this project...

Student Abbie explains her project's methods, including how to age flamingos by their plumage colour.

Student Abbie explains her project's methods, including how to age flamingos by their plumage colour.

Flamingos, like all birds, have excellent colour vision. Why invest so much time and energy into such vivid feather colour if you can't see it? Because the pinkness is all about finding a partner and being "useful" to the flock, young flamingos have to wait a while before they can breed. Therefore the adults aren't keen to let them take part in what the flock does. Abbie's data revealed that young flamingos are more likely to be found on the periphery of the flocks, and that another bird closest to them would be another young flamingo of a similar age. This pattern changed as the birds aged and as they got pinker. With the increasing pinkness of their plumage, so the flamingos were more likely to be seen in the centre of the flock.

In the thick of things at the moment, but as these chicks grow they will lose their place in the centre of the flock. Over time, as they turn pink, they will be allowed back in.

In the thick of things at the moment, but as these chicks grow they will lose their place in the centre of the flock. Over time, as they turn pink, they will be allowed back in.

Because flamingos as a species display extreme sexual selection (i.e. they do an intensive amount of courtship display and have their bright feather colours to attract a mate) they only want to associate with birds that are likely to be potential partners to breed with. Or they want to be in flocks with other birds that are ready to nest at the same time. Flamingos are well-known for only breeding when all birds are ready. This breeding behaviour is synchronised, in part, by the colours of the birds in the flock. So it is reasonable for them to not bother with other birds that are not pink. Young flamingos have to wait their turn and be patient; biding their time until they can show off the same bright hues as the adults and then take part in the breeding rituals and eventual nesting.

Colour change, pre- and post-breeding, is very obvious in Caribbean flamingos. In this photos, a new chick from 2017, stands behind a bird of a few years old. This older bird is mainly pink but still has "dirty" legs, and is nearer an adult bird. It is on the way of being more useful to the flock.

Colour change, pre- and post-breeding, is very obvious in Caribbean flamingos. In this photos, a new chick from 2017, stands behind a bird of a few years old. This older bird is mainly pink but still has "dirty" legs, and is nearer an adult bird. It is on the way of being more useful to the flock.

Abbie looked at the two flocks at WWT Slimbridge that breed most regularly. These two groups are also very large and therefore contain multiple, over-lapping generations. This means we can look across years at how individual birds change, and how they become more important to the flock's overall behaviour. Flamingos naturally have an erratic breeding cycle, so if only a few birds are in the mood to breed, it wont happen. Youngsters also learn from more experienced individuals around them. Research has shown that young birds spend less time displaying when compared to adults, and more time feeding. They need to build up energy levels for growth and development. By not joining in with the general activities of the main flock, they can prioritise behaviours important to helping them grow up big and strong.

It's already happening. The youngsters of 2017 have started to be pushed to the edge of the flock. It's a natural part of flamingo growing up. See them on the left-hand-side of this photo.

It's already happening. The youngsters of 2017 have started to be pushed to the edge of the flock. It's a natural part of flamingo growing up. See them on the left-hand-side of this photo.

I hope you've enjoyed this foray into the world of WWT flamingo science. Next time, I will provide some juicy stories on what Dimitrina has found out on the Andean and lesser flamingos from her our project. I am very proud of my students for the hard-work that they put into their projects. And that Abbie was able to present her results to a wider audience of zoo scientists and researchers is also very special. WWT flamingos have an important role to play in advancing our understanding of animal behaviour, and animal ecology, and why animals have evolved in the way that they have.